The death of libraries has many implications. Today’s libraries are not only about borrowing books, but are also important places for children to play video games, adults to complete homework, and communities to gather. In addition, libraries provide essential services to those who are marginalized by the digital world, including basic digital literacy training and access to Centrelink.

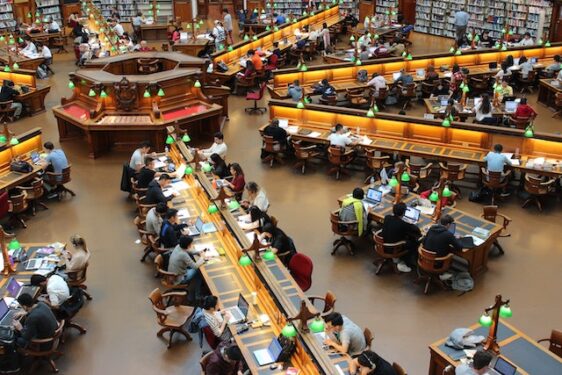

Libraries have long been the palace of the mind and University for all, and while the Internet has taken away some of the monopoly, it can’t replicate the sense of place that libraries give people. Andrew Carnegie, the first great patron of public libraries, envisioned a library in every town. Fortunately, that vision continues to be realized in progressive cities.

In contrast, libraries are in danger of experiencing a similar fate to churches. In rural areas, thousands of churches are sitting unused or virtually unoccupied. Their buildings and collections are underused, and they need communal nostalgia to survive. As a result, their numbers are on the decline. Libraries are also at risk of losing their cultural identity, if only because they are becoming less relevant to their communities.

Unfortunately, the future of public libraries in Australia is currently being written in contradictory double-narratives. There are one-off funding packages for ‘feature’ libraries, while libraries on the margins receive cuts. As a result, libraries’ expanded contribution to society is rarely acknowledged by government policymakers.

The government must act now to protect libraries. In the Dhaka metropolitan area alone, half of the community libraries closed in the past 12 years. The city had 27 community libraries in 2014. Of these, eight were run by the Dhaka city corporation – the south city corporation operated seven, while the north city corporation operated one. Yet the funds the community libraries receive are barely enough to purchase two newspapers and a magazine.